Tipped Issue #3

Cho Nam-Joo nails down gender inequality in her debut novel ‘Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982’ & the German-speaking world’s obsession with ‘The Isle of the Dead’

I had a nightmarish week, ridden with anxiety and nightmares following the brutal murder of Pinar Gultekin in Turkey. The young woman was one of the many victims of femicide in Turkey, which is currently planning to withdraw from the Istanbul Convention on the prevention of violence against women and domestic violence.

I feel terribly petrified and I am afraid I let anxiety take over me. I am trying to fight back through writing but everything feels just… Bleak.

I am sending love and strength to you, whoever needs to hear this.

Reading well

Reading time: 3 minutes

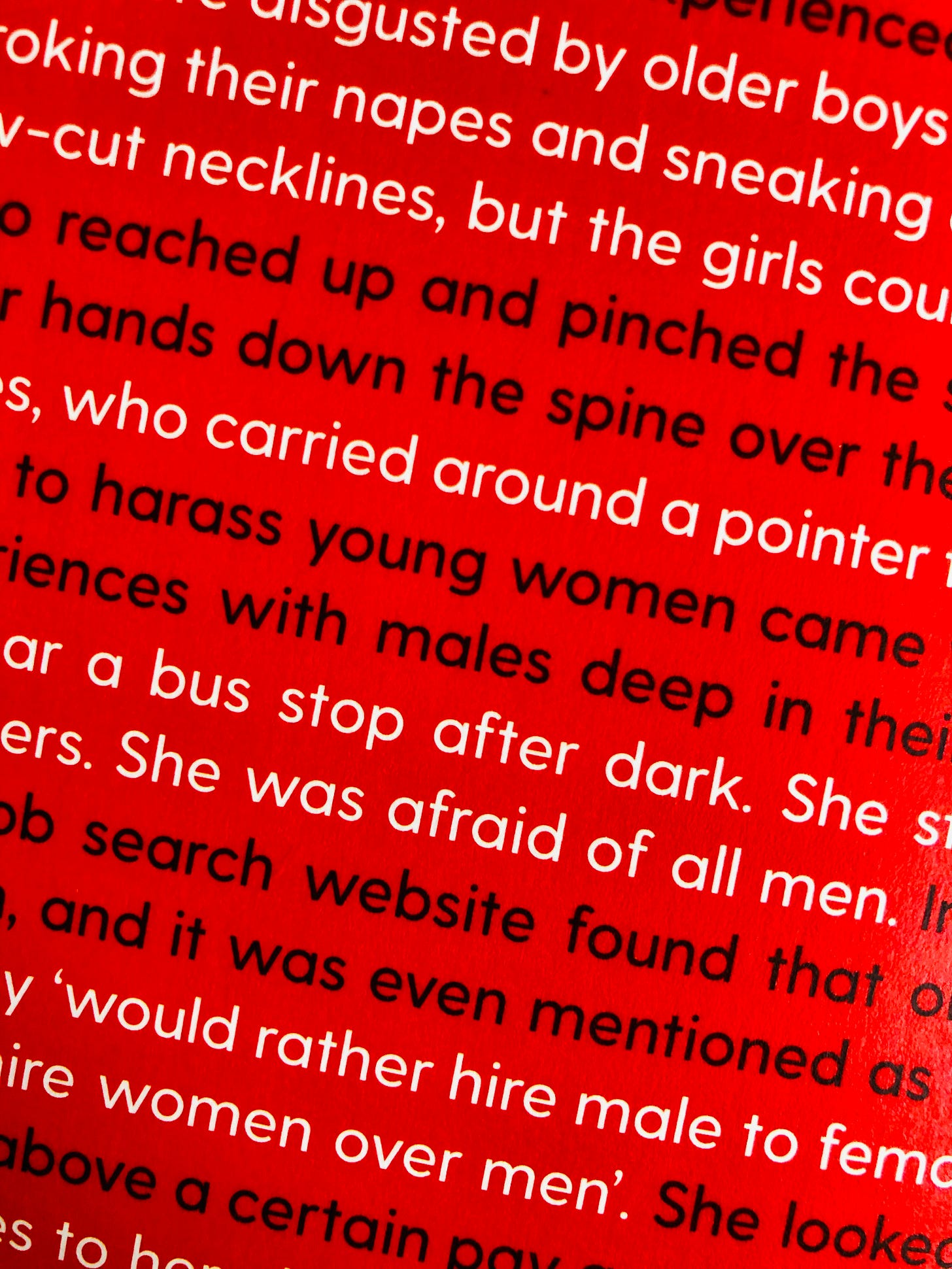

If you are a woman, you probably have a recollection of a boy who tortured you throughout the primary school, pulling your hair and throwing spit balls at you. Were there people, most probably adult women, telling you he did all of those things because he liked you? Or, a company did not recruit you because you could give birth in the future, therefore ~disrupt~ the workflow? The examples are specific yet so ubiquitous for women that reading these in a novel set in the modern South Korean context does not surprise me at all.

Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982. Simon & Schuster, 2020.

Cho Nam-Joo’s debut novel Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 became a cultural sensation when it was first published in South Korea four years ago. It follows the 30-something, frustrated housewife Kim Jiyoung (Jane Doe in Korean), as she is inundated with her responsibilities —housekeeping and childcare are one of the primary ones. She starts to take on personas, that of her mother, grandmother, and old friend as a coping mechanism. ‘Her abnormal behaviour’ embarrasses and creeps out her husband and his family. In a way, her switching to these personas in an anachronistic, incongruous way is annoying and unsettling the existing patriarchal structures and practices as she is betraying the order of whom she is supposed to be according to her age, role, and status. Basically, she is wearing the wrong paper doll cutout at the wrong time.

The author, Cho Nam-Joo for The New York Times

The novel is weaved as a clinical, chronological summary of Jiyoung’s life as we look into gender inequality that is so damn inherent in the South Korean society. We see Jiyoung and women in her life navigating this world that favours and serves men. As Jiyoung goes through her life from childhood to marriage, she provides an open access to the collective pains and familiar traumas of womanhood as the cornerstones of society are based on men thriving and women withering.

A still from the film —it was due to be screened as part of The London Korean Film Festival at the Barbican Cinema but got cancelled (yes, the pandemic).

Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 was endorsed by K-pop stars, translated into over a dozen languages, and adapted into a hit film (the actor playing the titular character received a record number of hateful comments on social media). Although the country has been enforcing laws around gender equality for some time now, it was only through this 150-page book that South Korean women started to question their mandatory paths disguised as ‘choices’. That ignition is the first step to a long journey of bringing down the patriarchy, and I am here for it.

‘I’m no longer accepting the things I cannot change. I’m changing the things I cannot accept.’ — Angela Davis

Gallery wall

Reading time: 3 minutes

In Despair, Nabokov wrote, ‘it could be found in every Berlin home’. A guide for newly-wed German women in the 19th century featured a copy of it. When moving to Basel, it was one of the few things Hermann Hesse took with him (in addition to Nietzche’s works). It was later acquired by Adolf Hitler to be displayed in the art museum planned to be opened in Linz. Lenin was known to be fascinated by it.

It is The Isle of Dead, a painting by Arnold Böcklin that gripped the imagination of the German-speaking world. The eerie yet oddly peaceful painting depicts an oarsman, quietly rowing, with a festooned object (that’s definitely a coffin), towards a small island.

The Isle of the Dead, Version III, 1883.

On the cliffs, we can see the sepulchral portals, somehow summoning the image of Japanese torii gates to mind. The cypress trees, which you can find in any European cemetery, hide the path to the unknown as if we, mortals with a beating heart, do not have access to what’s beyond.

So how did a painting so grave in context ensnare people? One of the reasons was a new printing technique, a major innovation that allowed quality reproductions and was quickly capitalised by publishing houses in the German Empire, therefore enabling the painting to make its way to households more easily. Another was that the painting spoke to middle class Germans’ newly-found appetite for the Mediterranean, which the long trees and the warm rocks of The Isle of Dead certainly evoked. The painting is also evocative of a rather peaceful, noble death in a century wrenched with wars and novel ways of brutal mass killing.

The painter Arnold Böcklin or commonly known as Gary Oldman/young Ataturk.

Despite the conversation and theories around The Isle of the Dead, the Swiss artist simply painted this for Marie Berna, a woman who was soon to remarry and become the Countess of Büdesheim after losing her first husband very young. Upon seeing Arnold’s work, Marie asked him to paint something that she could daydream over and remember her first husband by. Before one woman’s daydream became a mass adoration, Böcklin painted different versions of The Isle of the Dead, a total of five that are now hanging in the galleries around the world.

The Isle of the Dead, ‘New York’ Version, 1880.

Thanks to the success of The Isle of the Dead, there was no one who did not know who Böcklin was back in the day. He was held in high esteem, and his accomplishments were a beacon for both aspiring and established artists. Still, Böcklin fought a long battle with depression all his life as well as other physical illnesses, bore the loss of his first fiancé and many of his children. Maybe that’s the only meaningful reason why The Isle of the Dead was admired by many, because he was a man who unquestionably understood Death —he was the 19th century Charon, truly.

Bonus: Rachmaninoff’s The Isle of the Dead, inspired by the painting.

I hope you enjoyed this week’s ramblings. Don’t forget to recommend Tipped to your friends, and see you next week! 👹

Excellent content for morning coffee on a cloudy Monday morning, cannot wait for the next one!

Yet another great issue! Good idea with the reading time info :)