Imagine you are a woman poet in the 1930s - part II/III

Tipped Issue #7: Danish poet Ditlevsen on her Youth in her trilogy of memoirs

‘Happy and relieved and yet melancholy’: Tove Ditlevsen on her Youth

Reading time: 6 minutes

Last week, I left young poet Tove as she trudged through the streets of Copenhagen, rejected by an Editor who thought her poems were too sensual for her age. She stopped writing. I myself had years of practice in that area due to downright rejection by others and/or rejection scenarios I played in my head so vividly that I refrained from picking up the pen, ever. Some of the scenarios are downright brutal, like snuff films where I am both the victim and the executor.

As Tove counts the days until she leaves her parents’ house when she turns 18, she continues working as a maid, then as a trainee secretary. She throws herself into acting through which she meets a bubbly girl, Nina, a foil to her quiet, observant character. Her best friend ‘of the streets’ Ruth is out of the picture, and in comes Nina, good with boys, her eyes on the prize. While her virginity is considered ‘a defect to be remedied’, Tove’s concerns lie in securing a room of her own that she could write:

A room with a bed, a table and a chair, with a typewriter, or a pad of paper and a pencil, nothing more. Well, yes —a door I could dock.

Just like Virginia Woolf, she needs a peace of mind to write in the shape of a writing space, although modest, that will allow her to find her flow as she also finds out about ‘the indefinable difference between a good and a bad poem’. I remember my childhood poems, bursting out of my insatiable mind, ranging from tearjerker poems about my father to odes to my snot. I didn’t know whether they were good or not and I stopped writing poems when I came of high school age and learned about the greats —my writing was transformed from ruptures of creativity to benchmarking and comparing mine with others, who were light years ahead of me.

Tove finally gets her wish as their parents move to a larger house. She starts going out with Nina and is briefly engaged to a young man, whom she loses her virginity to, an event which is absolutely insignificant according to her. In a way, she rushes to adulthood, going past the checkpoints of adolescence one by one, because adulthood is where she will shine, free of the constraint of their family home, closer to her goal of becoming a woman poet. Ah, that feeling as if you are at the edge of your ‘real’ life.

She finally breaks off from her family, just after the world is shaken with the news of King Edward’s abdication and before Hitler invades Austria. She buys writing paper and rents a typewriter, living on nothing else but coffee and some pastry at a house owned by a Nazi-sympathising landlady. ‘Poverty is temporary and bearable’, she muses. She writes her poems while freezing as Hitler’s hellacious voice penetrates through her walls.

Wallis Simpson and King Edward, who abdicated to marry the American socialite

As the world comes to a boil, Tove meets a fellow poet and finds out about the literary magazine, Wild Wheat (Vild Hvede). Suddenly, the literary world she was only able to peek at only twice throughout her life opens its doors wide to her, as its Editor agrees to publish her poem “To My Dead Child”:

I never heard your little voice.

Your pale lips never smiled at me.

And the kick of your tiny feet

is something I will never see.

Tove did not have a stillborn child, instead the poem is about a young man she meets, who is going to Spain to fight in the Civil War, thus leaving a scintillating impression on her. Writing about him as he goes to die frees Tove of feeling sorry for him —she is ‘happy and relieved and yet melancholy’. Seeing her poem published in Wild Wheat produces the same effect, she is no longer anonymous, waiting for the world to find about her, happen on her. Yet, she is fired from her job because of her poem and is now left with the urgency to earn enough money to carry on writing. Taut with determination now that her path is clear, she ‘wants so badly to own her time instead of always having to sell it’, to which I say amen. That constant negotiation of time to be creative when you have to make a living is perhaps more apparent and gutting nowadays as corporate jobs are soul-sucking and demanding more than ever. How do you write the books you are meant to write when you work 40+ a week, appeasing KPIs and quarterly goals and having meetings that could have been emails? (I will never stop writing about the introvert’s tragedy.)

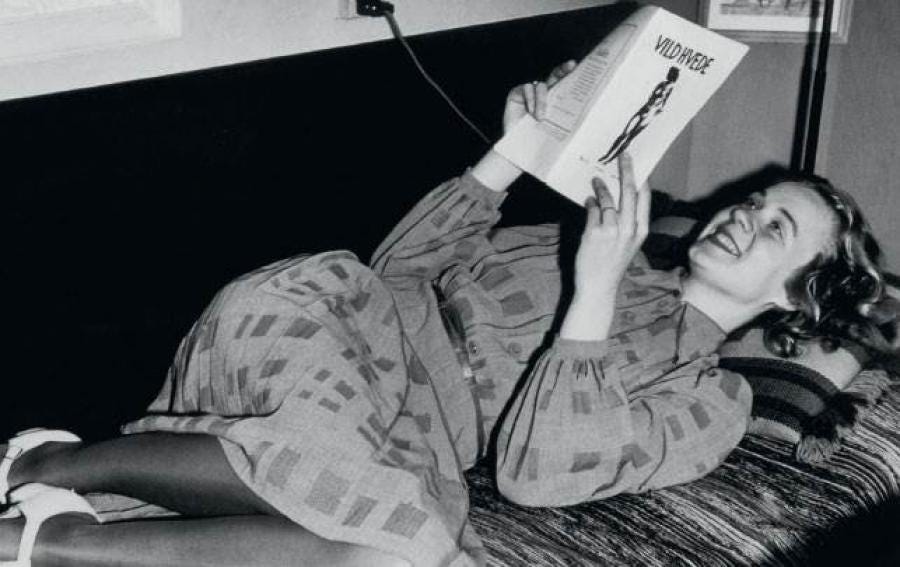

Tove reads Wild Wheat (Vild Hvede), a literary magazine that first published her poem, “To My Dead Child”

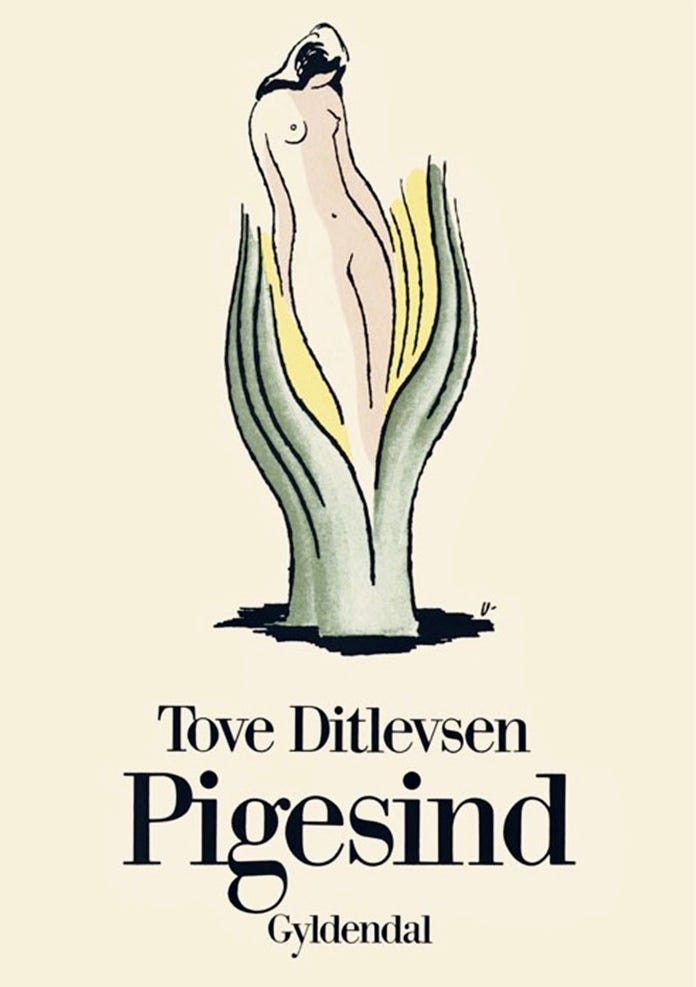

As England declares war on Germany and the world is falling apart, Tove has her poetry collection Girl-Soul (“Pigesind”) published, thanks to a writers’ fund enabled by the Editor of Wild Wheat, who will then become her first husband. Daily life goes on as if a World War did not break out, and her first book arrives in the mail:

My book! I take it in my hands and feel a solemn happiness, that isn’t like anything I’ve ever felt before. Tove Ditlevsen. Pigesind. It can’t be taken back anymore. It is irretrievable. The book will always exist, regardless of how my fate takes shape. (…) They [her poems] are strangely distant and foreign, now that I see them in print. I open another book because I can’t really believe that it says the same thing in all of them. But it does. Maybe my book will be in the libraries. Maybe a child, who in all secrecy is fond of poetry, will someday find it there, read the poems, and feel something from them, something that the people around her don’t understand.

As Youth ends and makes its way for Dependency, we see Tove as having made it to adulthood through her art, the base of which is constituted by her honesty and oddity, working-class background, and womanhood. Now onto the final book of the Copenhagen Trilogy, where drug addiction will take the centre stage of her life.

Hope you enjoyed this week’s ramblings —see you next week!

Loved it! Can’t wait for next week ♥️