Female Friendship in Elena Ferrante's Neopolitan Novels

Tipped Issue #10: True friendship is not always a source of strength and comfort. It is blood and plunder, too.

Hi all!

The moment I wrote ‘Tipped will be back on 4th October’ in the last issue, I knew that it wouldn’t -I wouldn't- and not writing it would be my baby elephant in the room that I will nurse and make sure runs away in my mind’s savannah in no time, which in this case took about a month. As well, taking time off from work and spending time with family required a cool-down period to recalibrate and ease back into my routine, which I thought was non-existent yet made its botchy mark on my life, very stealthily. I also worked on my writing: I fished out and marinated meaty ideas for my fiction writing during the holiday.

In short, Tipped is finally back! Thank you to those who asked when it’d be back, careful that I’d snap or snap your necks.

Female Friendship in Elena Ferrante's Neopolitan Novels

Reading time: 5 mins

Elena Ferrante’s novels are notorious for their hideous covers and typography that connote and scream genre fiction, which efficiently put me off for years (see below). Only when I read more about the enigma that is Elena Ferrante, her amazing translator Ann Goldstein, and interviews here and there that I realised I needed to dive in.

Elena Ferrante, whose early novels were celebrated in Italy with no international recognition, set out to depict the lives and friendship of Lila and Lenù set against the backdrop of Naples that is corrupt, unaware that it would take 4 books to do justice to their story. Aptly titled, The Neapolitan Quartet follows two girls, Lila and Lenù from their childhood in the 50s, effervescing with violence, patriarchy and territorial hierarchy that will shape their lives for half a century, to contemporary times where Lila disappears off the face of the earth. Confronted with the fact that she would never return, Lenù starts writing their lives through a painfully accurate lens with an aperture that could take in the darkness and intricacy of their characters.

New covers look much better.

Their friendship is built on contrast, Lila is fierce and feral, Lenù is silent and pensive, but they are united in their eagerness to outshine their families and neighbourhood. Their craving to learn and achieve more than anyone else, especially one another, creates tides between them throughout their lives as they make grave mistakes, push and pull each other, take a good beating from the volatile politics of Italy from the 50s to 90s. The first book, My Brilliant Friend, starts with 10-year-olds Lila and Lenù as they try to make sense of the cruel and chaotic world around them. Fights with their friends and teachers, violence and abuse from their families and neighbours, glimpses into ideal futures where they are rich and knowledgeable. Very early on, they fixate on getting rich through education as they live in a very hierarchical neighbourhood and immediately equate money with power.

Lila (left) and Lenù (right) on My Brilliant Friend on HBO. Image from Deadline.

Yet, circumstances command that they lead different paths: Lenù, despite all the financial and social challenges thrown at her, continues her education, whereas ever-the-tomboy Lila marries an influential young man in their neighbourhood. The Story of a New Name is thus centred around Lenù navigating the intellectual world repressed by her social class, and Lila, who enjoys newfound comfort and power through her husband’s wealth and her new identity as a married woman. Without giving too much away from the plot, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay deals with the aftermath of choices Lila and Lenù made throughout their marriages, their affairs and work as mothers, lovers, and citizens of Italy who are desperately fighting fascism and corruption. All gnarly, sometimes impulsive choices with great consequences.

The Story of the Lost Child sees two friends as they clash and fall out, then hold onto one another as they near their 60s, reviewing and picking apart their mistakes, looking back on what brought about Lila’s disappearance. Her disappearance is not abrupt but one she tried to pull off via numerous characters she assumes throughout the years; that of a wife, a lover, a factory worker, a business owner, a mother, and a historian. And Lenù, too, is a herstorian in the way she depicts their lives, the complexity of female friendship and sexuality, love and motherhood. Lila and Lenù are echoes of real women, ones that are strong and knowing, but also prone to oppression and malevolence. Ferrante says in Frantumaglia: A Writer’s Journey:

Many events in Lila and Lenù’s lives demonstrate that one draws strength from the other. But beware, this is not just in terms of solidarity, but also plundering each other, stealing one another’s emotions and wits, draining each other’s energy.

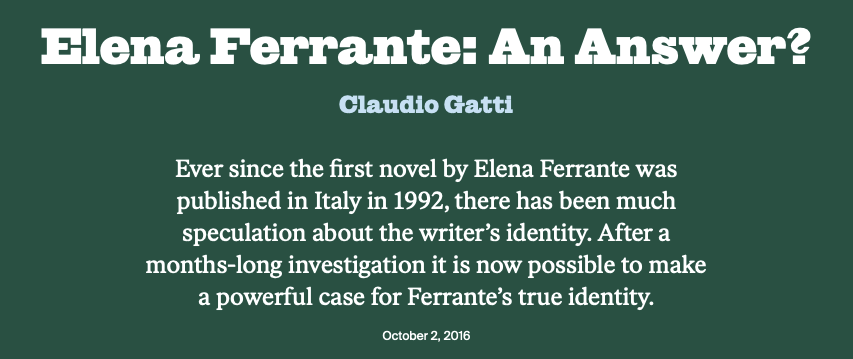

See the article published in The New York Review in 2016

The Neapolitan Quartet took the world by storm, and one expects Elena Ferrante’s face to be everywhere. Yet, we have no idea who Elena Ferrante is. No one knows who she is, and yes, Elena Ferrante is a pseudonym. Some, as Claudio Gatti above, tried to reveal her true identity: it is translator Anita Raja, or her husband & writer Domenico Starnone (or both). Clearly, it is disrespectful to her wish to remain this way, and the investigation and accompanying article on NY Review were quickly criticised by Ferrante fans around the world. Ferrante’s decision to remain a secret is a good fuck-you to the literary world that is marketing-obsessed and thrusts the celebrity of the author to sell more books. But it is also a refined tool to disappear in the text as an author, successfully divorcing herself from it. In her own words, her pseudonym allows her books to prove their autonomy to readers. ‘Books have no need of their authors’, she says, but clearly we need and will never get enough of Elena Ferrante.

Bonus: Elena Ferrante’s first book in five years after The Neopolitan Quartet is out. The Lying Life of Adults, of course translated by Ann Goldstein, is another bildungsroman following adolescent Giovanna in Naples as she transitions to womanhood:

Two years before leaving home my father said to my mother that I was very ugly. The sentence was uttered under his breath, in the apartment that my parents, newly married, had bought in Rione Alto, at the top of Via San Giacomo dei Capri. Everything—the spaces of Naples, the blue light of a very cold February, those words—remained fixed. But I slipped away, and am still slipping away, within these lines that are intended to give me a story, while in fact I am nothing, nothing of my own, nothing that has really begun or really been brought to completion: only a tangled knot, and nobody, not even the one who at this moment is writing, knows if it contains the right thread for a story or is merely a snarled confusion of suffering, without redemption.

Buy The Lying Life of Adults from The Bookshop, an online bookshop that financially supports local, independent bookshops. I am looking into setting up an affiliate shop here, so you might be getting some book lists from me in the future (although it only ships to the US and the UK at the moment).

Thank you for reading this far! I hope you liked this week’s ramblings. 🌸

Loved it!